4

The Visit Of Miss Victoria Formby

The rather less fortunate Joe Formbys of New Short Street had not seen very much of the John Formbys in recent years but they were well enough acquaint with the family to know which one Miss Victoria was. Cousin John’s note asking if his youngest daughter might spend a few weeks with the cousins was not, therefore, received with rapture. Though the good-natured Joe did say cheerfully: “One more little one won’t make no difference!”

“No,” agreed Julia. “Well, if she’s been jilted, poor girl, I dare say she’s so miserable that she is making a pest of herself, as Cousin John claims.”

“If you ask me,” said Captain Cutlass, narrowing her eyes—her family swallowed sighs—“Cousin Formby wants us to knock some sense into her.”

There was a short silence.

“Well, the word ‘pest’ was used,” admitted Niners. “I think you may be right.”

Lash looked round the parlour, bright-eyed. Suddenly she went into a helpless, wheezing, gasping paroxysm. Her brother’s eyes followed hers. He began to shake silently. Suddenly Aunty Bouncer gave a helpless yelp and collapsed in an alarming fit of cackles.

“Yes,” said Julia with a foolish smile. “I see what you mean.”

“’Specially—Cap’n—Cutlass!” gasped Lash helplessly.

Captain Cutlass looked down at her disastrous green baize garment. “This is a good—”

“Billiards table!” gasped Little Joe, breaking down in sniggers.

Baby Bouncer, or Ned, had been following the conversation with some difficulty. With relief he joined Little Joe in his sniggers.

“It cost—”

“We know!” wailed Julia, suddenly giving way completely. “Stop it—Captain—Cutlass!”

Captain Cutlass looked round calmly at her wheezing, gasping, cackling, sniggering and shaking family. “It is pointless to waste money on dress.”

Mrs Peters mopped her eyes. “If you don’t mind making a guy of yourself, girl, I’m sure I don’t know why we should care!”

Neither Niners nor Trottie True had sniggered, cackled, or even smiled. Now the former said seriously: “She takes it too far,” and the latter said: “She has a decent petticoat underneath, though.”

“Don’t start me orf again!” warned the old lady.

“No, stop it, girls,” agreed Julia unsteadily, blowing her nose. “Well, Aunty Bouncer, you will have to do the knocking of sense into Victoria, if that’s what they’re sending her for—and I do admit it sounds likely—because the rest of us are all clearly broken reeds!”

“Where shall we put her, Ma?” asked Mouse cautiously.

“She’ll be used to having a room of her own,” warned Niners.

“A girl of that age?” replied her mother dubiously.

“Yes! Miss Henderson says—”

At the same time Captain Cutlass and Mouse were chorusing: “Miss Henderson says—”

Julia waited until the expected outcry had died down and said: “Then I’m sure that must be right. But we can’t possibly; I mean, even Baby Bouncer, bother, I mean Ned, has to share when John-John is home from sea, and that room is so small one cannot swing a cat in it.”

“I don’t mind sharing with someone,” said Lash amiably.

“No, my dearest, you are a grown woman, and we will not sacrifice your comfort to a spoilt little girl from a mansion!” said Julia roundly.

Lash looked amazed, but nodded meekly.

“Mouse and I can easily squish up,” offered Trottie True.

“Yes: even though our bed is barely large enough for two, it will certainly be preferable to exposing the girl to the rigours of Niners and Captain Cutlass,” agreed Mouse primly.

“Hah, hah!” they cried crossly.

“Bung ’er in my room, on the truckle bed,” grunted Mrs Peters.

Aunty Bouncer snored terribly: Julia gulped. “Um, no, Aunty, there’s no reason you should be the sacrifice, either.”

“We could fit in another,” said Niners calmly. “And if she can’t stand us, too bad.”

Julia hesitated. Niners was relatively normal, barring the obsession with independence and the intensive studying of every blessed thing in Miss Henderson’s ladylike house—but Captain Cutlass? A girl that wore green baize bought for a groat for ten ells at the market, and insisted on learning Latin and Greek? And last summer, when it had been very warm, she had cut off her hair like a boy’s, remarking that it was the only sensible move in such sticky weather and that there was no rational argument for wearing it long. It had still scarce grown out and in fact was shorter than Ned’s.

“The little lad can go in with Little Joe; give the girl his room,” said the old lady.

“I don’t think that would be fair, Aunty,” replied Julia firmly. “Ned is part of the family.”

“She’s right,” agreed Joe, unexpectedly entering the lists. “Added to which, what if John-John comes back from sea?”

Captain Cutlass began: “Well, it wouldn’t necessarily be an unpleasant shock to find Victoria in his b—”

“That’ll do,” he said, grinning. “He’ll want to feel this is still his home, we can’t do that to him. The girl’ll just have to take us as she finds us, Julia, love. And there’s plenty of room in with Niners and Captain Cutlass. If she don’t fancy sharing the big bed, we can put the truckle bed in there for her.”

“Very sensible!” approved Mouse, laughing. “Settled! –I’ve finished this novel, it was stupid. Don’t give it a good leather, Pa.”

“They only want it half-bound,” he said mildly.

“Good. Well, what can I read?”

“There’s a whole set of sermons in at the shop,” said Joe with a twinkle in his eye.

Mouse having refused this offer with horror, Captain Cutlass helpfully searched on the worktable at her elbow. It held no work, she was not talented, but a great pile of books, the bindings in poor condition. Unfortunately Dr Adams could not afford to have them repaired, even though Pa had offered him a very good rate. “Here: Marcus Aurelius—”

“Not Latin, Captain Cutlass,” she groaned.

“No, it’s a translation. Not bad. You will like it, he has sense,” she promised.

Mouse raised her eyebrows but took the book.

Silence reigned in the Formby front parlour, though from time to time Joe, who was re-reading Tristram Shandy (full calf, T.E.G., quite a nice commission from a man who had inherited an old uncle’s library), emitted a muffled chuckle. Captain Cutlass frowned over Marcus Aurelius in the Latin, occasionally mouthing a phrase over to herself. Trottie True was re-reading Sense and Sensibility: she alternately smiled and shook her head reprovingly. (Full calf, T.E.G., the same commission.) Julia was struggling with a lady’s account of her travels to India, via Egypt and various hot and presumably sandy places in between. They were not very well described at all and it was extremely hard to guess where the lady was, most of the time. Though the Oriental potentates were fairly thick upon the ground, those bits were impressive. (Russia leather, binding requiring mending only.) Niners was absorbed in a volume of household hints belonging to Miss Henderson. Lash worked on her embroidery for a while and then also took up a book, what time Mrs Peters, not such an avid reader, nodded over her knitting.

After some time Little Joe looked up from Ivanhoe (full calf, T.E.G.) and said: “I think Ned would like this. We might try him with it after Robinson Crusoe, Aunty Lash.”

“Too much love. Added to which, Ivanhoe is the greatest looby who ever walked.”

“I wouldn’t say that!” replied her nephew, very startled.

The heroes created by the delicately clever pen of the Lady of Quality not being, by and large, favourites with the Formby women, Mouse murmured slyly: “No: I thought that honour was Mr Bingley’s?”

“Huh!” agreed her aunt with feeling. “Very well, Bingley and Ivanhoe make a pair.”

“You’re not re-reading Pride and Prejudice, Lash, are you?” asked Julia uncertainly. “Didn’t you say just the other day that Darcy was a stuffed shirt who could not get one a chair in the rain? And if Bingley is a looby—”

Before Lash could answer, Captain Cutlass said: “No, but Ma, I tell you who could get one a chair in the rain, and that is Eliza Bennet!”

“Yes,” agreed Lash calmly, while most of them were still gulping. “No, well, it is so well written, you see, Julia.”

Julia subsided into the lady traveller’s work, smiling weakly.

… “You know,” said Joe to his wife as they settled into bed that night, “Lash has improved, if she really did spot that Darcy is as much of a piece of wet flannel, underneath the lord of the manor rubbish, as Bingley.”

“Well, yes, she did say to me that she doubted that Darcy could get one a chair in the rain, in spite of his grand airs. Though as she’s never taken a chair in her life, I’m sure I don’t know where the image came from!”

“Those books, I suppose: they’ve all been re-reading ’em.”

“Mm. –It would be nice to have our own copies.”

Joe would read anything, but truth to tell the only character from the works of Miss Austen whom he really enjoyed was Mr Collins. “Uh—well, see what I can do, love. But don’t you think Lash has improved, to come out with something so practical?”

“Yes.” Unfortunately practical, sensible men of the sort who could get one chairs in the rain were pretty thin upon the ground, in Waddington-on Sea. Julia didn’t say so: Joe was more than bright enough to have thought of it for himself.

Miss Victoria Formby’s introduction to Number 10 New Short Street was not entirely auspicious. In fact she arrived, escorted by both her father and her eldest brother, Johnny, around midday, just as the Mountjoys’ much-anticipated new bed arrived at Number 8. And was duly scandalised by the sight of several of her cousins out on the pavement watching. Or in the case of the peculiar cousin with the very short yellow hair, assisting. Until a young man in shirtsleeves said with a laugh: “Get off it!” At which point Victoria’s own papa got down from the carriage and rushed over and joined in!

The blenching Victoria squashed herself into the furthest corner of the carriage, ignoring the subsequent shouting and screeching, though she did register with relief the disappearance of the peculiar cousin to fetch a carpenter to dismantle the giant bed. And remained there, regardless of the fact that her brother was looking out eagerly, sniggering from time to time, until her infuriating male parent flung the carriage door wide, said cheerfully: “Out you come!” and positively hauled her down before a small, crooked house in a row of small, crooked houses in a very narrow, crooked little street.

“You said it was a new street!” she hissed angrily.

“Huh? No, no, the name dates from the Middle Ages. Differentiates it from Old Short Street, y’see: that’s even shorter: runs off the end of the street, there, see?”

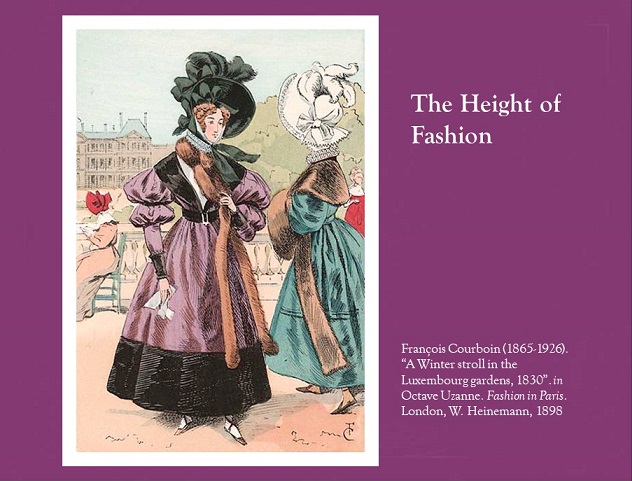

Miss Victoria tossed her fashionably bonneted head, and did not look.

“You remember your Cousin Lash, Joe’s little sister, don’t you?” he said, putting his arm around the older woman’s waist. –No cap. At this hour of the morning? “Well, she were christened Lavinia, and you might’ve heard your Ma use the name, but nobody else don’t, I can tell you! –That were Captain Cutlass what rushed off to fetch the carpenter, think you met her before, hey? And this pretty little one is Marianne, that they call Mouse!”

It was no surprise at all, after that, to discover the front parlour was empty. Victoria’s impossible father sat himself down on a sofa without being invited to. “Sit down, Victoria, don’t stand on ceremony!”

Victoria was still giving him a cold and would-be meaningful look, when Cousin Lash, seconding the invitation to be seated, rushed out in search of Cousin Julia.

That left Mr Formby, his two children, and the so-called “Mouse.” How a girl could support that nickname when she had a lovely name like Marianne—!

“We didn’t think you’d make it by midday, Cousin Formby,” she said.

“Nor did I, lass,” replied Victoria’s impossible father happily. “Victoria, here, didn’t have hardly nothing packed, or that was her story, so I bunged her into the carriage whether or no, and came. We can always send over any clothes she may have left behind—that is, if you’ve got the ten dozen wardrobes to accommodate ’em!”

Victoria went very red, but said nothing. There would be at least one member of the family who would not let herself down today!

“Well, you won’t need many clothes here, Victoria, because we don't lead a fashionable life,” said Cousin Marianne.

“I assure you I have brought sufficient with me, Cousin Marianne,” said Victoria stiffly.

“Um—yes. Have you? Good. Um, would you mind awfully not calling me that? Everyone calls me Mouse, and really, she was the silliest goose, wasn’t she?”

“Wh—who?” faltered Victoria. It must be some old cousin of whom Papa had never told her, and it was too bad of him!

“Marianne Dashwood, of course,” she said, smiling at her. “Though one cannot help liking her, all the same!”

“I’m sorry, I have not met many of Papa’s side of the family, Cousin Mouse,” said Victoria stiffly.

This was apparently the wrong response, though Victoria could not see why: Mouse swallowed, tried to smile, and fell silent. Johnny then made some stupid joke and started to talk about books, and ask for whom all their cousins were named—as if it could possibly signify! Papa, of course, joined in, insisting on telling her about their own older sisters and younger brothers—really! And it was not at all intriguing that they both had sisters called Theresa, and why one should pervert a perfectly acceptable name like that to “Trottie True”! But then, a family which allowed a daughter to call herself “Captain Cutlass” was doubtless capable of anything.

Then one of the old great-aunties came in. Victoria knew what to expect, which was just as well, because the bent old woman was as usual in an apron over rusty black, and huddled in a knitted shawl, with a big mob cap. And a female could not be called Bouncer, and at her age, it was completely unseemly to go on using it!

“We met Captain Cutlass,” Johnny was explaining. Purely for the pleasure of using the ridiculous name: could they not see that? Victoria directed a bitter look at him.

Great-Aunty Bouncer sniffed. “Fancies herself a handyman. I said to ’er, why don’t you take that Trickett, if you’re that keen on hammers and nails? But she ain’t interested.”

“Not interested in Trickett in particular, ma’am, or not interested in men in general?” asked Johnny dulcetly.

“Not in Trickett, that’s for sure! Never seen ’er take no interest in nothing in fancy pantaloons, neither, if that’s what you’re asking,” she noted, eyeing his drily.

Hah, hah, hah! Victoria almost smiled, Johnny was looking so disconcerted!

Mouse then excused herself and went to see what was keeping her mother, and Johnny, who had not the sense to know when to keep silent, pursued: “Pray tell me, Aunty Bouncer, was the dauntless Captain Cutlass wearing green baize, or did my eyes deceive me?”

Mrs Peters gave him a sour look. “So sharp he’ll cut ’imself one of these days,” she said to his father.

“Exact. –Drop it, Johnny, you ain’t funny.”

“I do beg your pardon, Aunty Bouncer,” said Johnny smoothly.

She sniffed, but appeared mollified, and volunteered the far-from-intriguing information that Julia was doing her foreign fish soup, the receet they had had off Joe’s and John’s old Gran. At this, Victoria’s dreadful parent became vastly excited, asked if he might look, and rushed out to the kitchen! Whereas he never so much as set foot in their kitchen at home! What had come over him?

That left the fancy-pantalooned Johnny and the fashionably bonneted Victoria alone with a funny old woman in a cap and apron.

It was hard to imagine precisely how it could get worse, but of course it did. The table manners of such persons as the carpenter in his leather apron, who actually ate with them, the old great-uncle—they did call him Nunky, her ears were not deceiving her—or Cousin Lash’s little boy, being not the least of it. There was no footman, of course: Cousin Julia and Cousin Lash bore in the dishes themselves. But at last the dreadful meal was over and Victoria could retire to her room.

“This is very kind, but I did not bring my maid,” she said, seeing the small bed set out by the side of the larger.

“What? Oh,” replied Mouse numbly. “Yes. Good.” Numbly she ascertained that her cousin had everything she needed, and, Victoria intimating that she would care to rest for a little, tottered downstairs. “She’s lying down,” she reported to the group in the front parlour.

“That’s all she’s done in the six months since that little worm, Darrow, ditched her,” noted Victoria’s father grimly. “Not bawling, is she?”

“No.”

“Count your blessings, then.”

“I’m sure,” said Julia firmly, giving Mouse a warning look, though aware that at the same time she was giving her a desperate one, as of one wishing to convey an urgent message, “that the poor child is welcome to lie down whenever she wants to. No-one will bother her, John.”

“No, well, dunno that I wouldn’t rather you did bother her, but so long as the girl don’t make a nuisance of herself! Now, think Johnny and me might walk off the most delicious meal I’ve had these past twenty years and more by getting on over to the shop, hey?” Forthwith he led Johnny out.

“What, Mouse?” said Julia immediately.

“Victoria is laid down upon the big bed. She seems to think the little one was intended for her maid!” she gulped.

“She’ll get a shock when Niners and Captain Cutlass get in beside her, then, won’t she?” said Julia placidly.

Later that afternoon, when Julia, Lash and Mouse came home in a bunch from a foray to a strange baker’s, their local baker having run out of anything that struck the eye as likely to appeal to the visitor’s stomach, Miss Victoria and Master Yates were discovered in the front parlour, comfortably reading Ivanhoe.

Mouse just stood there and goggled.

“Ivanhoe?” croaked Lash. “Isn’t there too much love in it for him, though?”

“No! It’s good!” he cried shrilly.

Victoria smiled uncertainly. “I am skipping any, um, silly bits.”

As Lash recalled the thing it was largely silly bits. “Oh. Good,” she said feebly.

Julia was also goggling, though not for the same reason. A small, grimy, black and white dog was also present in the front parlour. “Where did that dog come from?” she croaked.

“Ned said he came home from school with him: is he not his?” replied Victoria feebly.

Julia tottered over to the sofa and collapsed on it. “Never saw him before in my life!”

“Oh, Ba—Ned,” said his mother sadly.

“He followed me!” he cried shrilly. “He was looking for a home!”

Lash investigated. “No collar. All the same… Oh, well, Ned’s mine, it had best be me that tramps for miles along the route to school and all its possible byways looking for the creature’s owner—and believe you me, the byways that are possible to the eight-year-old brain are many and various!”

“You can’t possibly, Lash, it’s getting dark,” said Julia firmly.

Mouse squatted and examined the little dog narrowly. “He’s in poor condition: you can see his ribs. I think he is a stray, Aunty Lash.”

“Yes, ’cos he was really hungry!” ventured Ned.

Lash shut her eyes. “What did you give him?”

Ned had given him the heel of the loaf and “a small piece of meat.” His family made a concerted rush for the larder. Victoria looked at him limply. Ned stared back defiantly.

Mouse tottered back. “It was the piece of steak Ma held back from the big pie she made for dinner, because tomorrow she’s intending to do a vegetable stew—that’s a ragoût, to you, Victoria—and Great-Nunky Ben hates it. The meat was going to go in a little pie for him. It could have been worse: the liver for tonight’s supper is untouched.”

Victoria tried to smile. “He—he must have given it him before I came down.”

“You don’t say. It’s all right, Ba—Ned, you’re forgiven. Did you give the dog some water?”

Yes, and he had lapped it all up was the answer.

Mouse was about to disappear again so Victoria confessed quickly: “Mouse, I—I gave Aunty Jicksy a cup of soup with a spoonful of brandy in it.” Omitting the details of the horrid shock it had been to wake and find herself in a house that was deserted except for the little old russet-cheeked woman sitting up in her bed. And the equal horrid shock it had been to realise that Great-Aunty “Jicksy” expected her to venture alone into the kitchen.

“Oh, good! She’s feeling brighter, is she?” responded Mouse.

“I—I think so. She said a cold takes it out of one, but she did seem quite bright. And, um, I gave Ned a spoonful of treacle and some soup,” reported Victoria.

“That’s good! At least he had the sense to ask, not tackle the treacle by himself!” Mouse disappeared again.

Victoria looked helplessly at the two culprits. The little dog put his chin on his new master’s foot and sighed, and Ned just looked back at her blankly.

“Um, shall I go on?” she ventured.

He brightened. “Yes, please!”

Limply Victoria got on with Ivanhoe, valiantly doing her best to leave out the silly bits.

Mr Formby, after a fascinating afternoon spent with Joe at the shop, had given in to the temptation to stay on for supper with his cousins, but had removed himself and Johnny shortly after the meal. “When we left,” he explained to his wife with a twinkle, “Lash was working on her embroidery, Aunty Bouncer was knitting, and the rest of ’em were settling down to their books!” He shook silently.

“Books?” said Belinda Formby faintly.

“Aye! And you will never guess how Victoria spent the afternoon!”

After something over six months of it, Mrs Formby’s guess would have been, sulking in her room. “Er—how, my dear?”

Sniggering, Mr Formby revealed: “Reading to Lash’s little boy!”

“Ned,” explained Johnny languidly. “Or, possibly, Baby Bouncer. –Ivanhoe.”

“Ivanhoe?” she croaked. “But she refused to read my copy of that: she said it looked silly and Mediaeval!”

“I would not have known the word was in her vocabulary,” murmured Victoria’s brother. “No, well, ’tis silly and Mediaeval—nevertheless.”

Mrs Formby looked helplessly at her husband.

“I ain’t saying,” he said dispassionately, sounding for all the world like Aunty Bouncer or Lash themselves, “that it’s goin’ to turn her into a reader.”

“No,” said Victoria’s mother faintly.

“But I will say, it’s a dashed good sign!” he said with feeling.

Mrs Formby could only nod weakly.

Victoria woke betimes the following morning—quite possibly because of the sleep the previous afternoon. Beside her, Niners was lying on her back, snoring. In the little bed, Captain Cutlass was awake, watching her. Laying a finger to her lips, she made vigorous gestures and got out of bed. There was nothing to say what time it was—her cousins’ room did not feature an elegant gilt clock as her own did. So Victoria got up, perforce.

Downstairs, Captain Cutlass headed straight for the kitchen. Limply Victoria followed her. None of the family were present except Ned, seated at the old scrubbed wooden table, eating something from a bowl. At the stove was a large, red-cheeked woman.

“This is Cookie,” explained Captain Cutlass, putting an arm round her mountainous person and dropping a kiss on the big red cheek. “Though I dare say she won’t positively object if you address her as Mrs Dove. –This is Victoria, Cookie.”

“Pleased to meet you, Miss Victoria, I’m sure,” said Mrs Dove amiably.

It was the very first time Victoria had ever been introduced to a cook. “Huh-how do you do, Mrs Dove?” she said faintly.

Mrs Dove appeared to think that this conventional enquiry warranted a reply. “Not so bad at all, thank you, Miss.”

“The reason that you did not meet her yesterday,” explained Captain Cutlass—“aside from the fact that she was not here, of course—”

“Give over, Captain Cutlass, deary!” Mrs Dove adjured her.

Grinning, Captain Cutlass explained: “Was that it was her day for spending with her ma, Mrs Moon, and spelling her widowed sister, Mrs Mary Gubb, who lives with the old lady.”

“I see,” said Victoria faintly.

“It were that, deary, and I brung back some fine speckledy eggs from Ma’s ’ens, so if so be as you fancy a h’egg to your breakfast, there’s plenty.”

“Or a piece of eggy bread, that’s good, Victoria,” contributed Ned.

“No, I—perhaps just a slice of bread and butter, thank you, Mrs Dove.”

Mrs Dove assenting, and firmly squashing Captain Cutlass’s counter-suggestion of the fried eggy bread, bacon and sausage that she was going to have, there seemed nothing for it, since her cousin was swiftly setting two places next to Ned’s, but to sit down in the kitchen.

“I thought,” said Captain Cutlass, having engulfed vast quantities, “that we could get out and see if someone along the tortuous track to school might have lost a small black and white dog, putatively a terrier-cross.”

“No-o!” wailed Ned.

“Yes. Someone may have cried their eyes out all night, missing him,” she said sternly.

Ned attempted to argue, but was overborne. His mother came in yawning and supported Captain Cutlass’s stance, but tried to insist on going in their stead—an offer which Victoria would gladly have accepted—but was also overborne.

So Captain Cutlass, in a battered grey cloak over her usual green baize, and a coal-scuttle of a bonnet that looked more suited to a person of Mrs Dove’s age and class, Miss Victoria in her good violet pelisse and silk bonnet, Ned in his school clothes and sturdy boots, and the little dog (now named Dog Tuesday, since yesterday had been), prudently on a lead, all set forth for school. Accompanied by Mrs Dove’s parting shot: “You gotta get up earlier than that in this ’ouse to outwit Captain Cutlass, me lad!”

“Right,” stated Captain Cutlass grimly, maintaining an iron grip on Ned’s hand with the hand that was not gripping Dog Tuesday’s lead: “you’re going to show us exactly what route you took home from school yesterday! –Failing that,” she explained to Victoria, “we’ll simply drag him on every possible route; too bad if it makes him late for school and Miss Finch administers a sound beating.”

“You’re real MEAN, Captain Cutlass!” shouted the red-faced Ned.

“Yes. Go on, which way’d you come?”

Ned had come up Old Short Street, though that (quickly) wasn’t where he’d found him!

They dodged between two old houses leaning together and went into the narrow, dark, cobbled little street. It was very steep, and Victoria, who had not bothered to look about her at all yesterday, now began to wonder if perhaps they were very near to The Front: she certainly thought she could smell the sea.

“Micky Trickett went straight home,” said Ned on a sour note.

“Uh-huh. HOY! Micky Trickett!” bellowed Captain Cutlass.

After a moment the door of one of the huddled, crooked little houses opened and the thin-faced Micky Trickett appeared, chewing.

“Were you with Ned when he found this dog?” demanded Captain Cutlass without preamble.

“That was yesterday,” said Micky Trickett in a self-exculpatory tone.

“Exact. Were you?”

Micky Trickett admitted he had been.

“Right. Where was it?”

“Um, dunno,” being the answer, Captain Cutlass bellowed: “HOY! Mr Trickett!”

The carpenter appeared in his shirtsleeves. Victoria went very red and was unable to utter.

“These two monsters stole this dog yesterday on their way home from school,” said Captain Cutlass without preamble.

“We did not!” wailed Ned. “He’s a stray!”

Mr Trickett scratched his unshaven chin. “Want me to dust their breeches for ’em?”

“If they won’t tell us where they found him: yes,” agreed Captain Cutlass cheerfully.

“Well?” said Mr Trickett unemotionally to his offspring.

“It were down along The Walk,” said Micky sulkily. He stuck his narrow little chin out. “An’ Mr Jenks, he come out of his shop an’ said it was a stray what hangs round stealing, and if he saw it round ’is place again it was for the chop!”

“So you two gubbinses took it upon yourselves to rescue it,” said Mr Trickett with a sigh. Victoria was not absolutely sure what a gubbins was, but she got the general drift, and nodded her fashionable headgear hard. Mr Trickett glanced at her in some amusement, but said calmly to Captain Cutlass: “Don’t think that were a lie: ’e does know how hard my hand is. Old Jenks’ll be open: I’d cut along down there and ask him, if I was you.”

“I will. And I’ll forbear to ask,” she said, giving Ned an evil look, “how the route home from school took you two down the far end of The Walk! –Opposite direction,” she said briefly to Victoria. “Right—come on. Ta, Mr Trickett!”

“Any time,” said Mr Trickett unemotionally, drawing his offspring inside with one casual movement of his well-muscled arm.

Old Short Street did lead down towards the water: it rapidly debouched into another street, equally narrow but almost as steep, and after rounding a couple of bends—and incidentally bestowing friendly greetings on the odd tradesperson, woman with a basket, and so on whom they happened to encounter—Captain Cutlass announced: “The Walk!”

“I see,” said Victoria. The Walk adjoined The Front, and bordered the western side of the bay on which sat Waddington-on-Sea. “This is the Old Town, then.”

“Of course! Come on, Mr Jenks’ shop is along here.” She set off at a brisk pace.

The butchery was open—at least, its door stood wide, though the shop itself was empty. “HOY! Mr Jenks!” And the two girls went in.

“Be with you in two shakes!” came a voice from the hinterland, and after a moment a burly, red-cheeked, dark man in a butcher’s apron appeared, bearing a large piece of meat, which he dumped on the block next his counter. “’Morning, Captain Cutlass!” he said cheerfully. “Your ma fancy a nice leg of ’ogget today?”

“Not today,” said Captain Cutlass on a grim note. “We’ve come to find out if you know where Ned found this dog. HOY! NED! Get in here!”

Forthwith a sulky Ned and an eager Dog Tuesday appeared.

“That’s that ruddy stray!” cried the butcher. “Don’t you imaginate you’re going to dump ’im back ’ere, young shaver!”

“We’re not dumping him,” said Captain Cutlass kindly. “So he is a stray?”

“Aye. Been ’anging round ’ere… Now, two weeks, at the least, I’d say. HOY! JEM!”

A gangling aproned youth with a shock of black curls appeared, grinning. “What, Dad?”

“’Ow long as this ’ere blasted dog been ’anging round ’ere a-begging and a-stealing?”

“Three weeks? Since Mrs Mitcham come in after sweetbreads for ’er dinner-party.”

“See?” cried Ned.

“Yes, I’m convinced. You can keep him,” allowed Captain Cutlass.

“Huzza!” he cried, doing a short dance of triumph and letting go the lead.

“Oy!” shouted the youth.

“Grab ’im!” yelled the butcher.

Captain Cutlass, more practically, flung herself upon the dog and the giant piece of meat which he had sunk his teeth into and dragged to the floor off the very butcher’s block itself.

“It’s all right,” she said, dusting herself off and disengaging Dog Tuesday’s teeth from the meat. “Bit sawdusty, that’s all.”

“And got ’is teethmarks in it!” said the butcher with justified annoyance.

“Cut that bit off and I’ll pay you for it,” said Captain Cutlass resignedly. “And, um, better let us have a few bones for him, I suppose.”

A nice slice of hogget was duly cut off the haunch for the undeserving Dog Tuesday, Master Jem Jenks fetched a giant selection of meaty bones, and the Formbys retreated in relatively good order from Mr Jenks’ shop. Though with the butcher’s promise that if he ever saw the flea-ridden cur round here again he’d take his big chopper to him.

The girls then accompanied Master Yates to school, where an affecting farewell took place between him and Dog Tuesday.

On their return to the house it was revealed that Cousin Julia was gone to Miss Pickles for her drawing lesson, since it was Wednesday, and that the next thing to do was make the beds.

“Do you have no help in the house at all, save Mrs Dove?” said Victoria faintly, when at last all the beds were made.

“Mrs Weeks comes in three mornings a week to help with the rough work, and there is Polly Patch, but she’s laid up with a broken leg,” explained Captain Cutlass. “Ma said it would be unfair to replace her in the meantime: it’s not her fault she broke her leg.”

“No,” she agreed faintly. “Wuh-well, what are you going to do next, Cousin?”

“Some Greek for Dr Adams. You could come: he’s only at Number 3.”

Victoria licked her lips. “Well, I— Does he have a hostess?”

“No, he’s only a lodger. Mrs Lumley will be there, unless she’s gone to the shops.”

“I—I do not think I ought,” faltered Victoria. “Mamma would not care for it.”

Captain Cutlass was about to say that Dr Adams was harmless: then she remembered the defrocking story. “Just as you like. I’ll see you later, then!” And with that she vanished.

Victoria bit her lip. Everyone seemed to be out. She ventured along to the kitchen. Aunty Bouncer was in the rocker, knitting, and Mrs Dove was at the stove. Amiably the cook offered her a cup of tea. Even Miss Victoria Formby did not make the mistake of asking for it to be sent along to the parlour. Meekly she sat down at the kitchen table.

Next chapter:

No comments:

Post a Comment