7

Family Matters

Richard Baldaya’s feelings were somewhat turbulent: he had been telling himself all morning that there was little likelihood of bumping into Miss Marianne a second time, but had been unable to prevent himself hoping. This in spite of the fact that he had previously decided to put her right out of his head. She was a delightful little thing but the family, if respectable, were small-town nobodies; and this morning’s encounter most certainly reinforced the point. Well—the mother doing her own shopping? His friend Bungo’s reaction to this second meeting only confirmed his opinion that it would not do. He experienced considerable relief when Jack and Poulter took Miss Marianne off to look at curiosity shops. Possibly he and Bungo should have offered to escort Mrs Formby home, but he refrained from making the offer and Bungo, thank God, did likewise. They went silently back to the yacht, where oddly enough Luís did not bore on unendingly to them about ducks, pigs and similar rubbish, but remained in the little wheelhouse with Captain Richards.

They had to wait until the damned brat got back with her purchases, of course, but at long last were able to return to Sunny Bay and thence Stamforth Castle. Where he went quickly upstairs, avoiding his sisters, and shut himself into his room.

Bungo had had no opportunity for private speech with his brother on the boat: Luís took the wheel and Jack immediately came to assist him; but as Luís was now staying at the castle, he buttonholed him in his room as he was changing his clothes. “Look here, Luís—”

“Hullo, querido. You have changed already? That was quick.”

Bungo’s square jaw hardened. “I’m not a certified Pink, unlike some. Though the appearance you presented this morning would certainly excuse the Formbys for not having realised it!”

Luís was in his shirtsleeves, tying his neckcloth. He said nothing, concentrating on the neckcloth. “Pretty, no?” he said finally, admiring his appearance in the mirror. “It’s a fashion I picked up in Paris, I have not seen this precise style in England.”

“Right: why don’t you favour the damned Waddington-on-Sea market with it, Luís?” snapped his younger brother crossly.

“It would be highly unsuitable for the market,” replied Luís simply. He picked up his watch from the dressing-table and slipped it into his waistcoat pocket.

“Is that a gold watch?” said Bungo feebly, allowing himself to be side-tracked in the Ainsley manner.

“Sí.” Luís drew it out again and showed it to him, smiling. “Very pretty, no?”

Bungo drew a deep breath. “Very. Who gave it you? That Jeffcott dame that Gaetana was on about? Mme de Villemorin? Ana Molina y Alcalà Galiano, perchance?”

“You are quite wrong,” he replied calmly. “In the first instance, Lady Jeffcott is not in the habit of bestowing valuable presents, whatever else she may be in the habit of bestowing.” He eyed him sardonically: Bungo’s fair skin had gone very red. “In the second instance, I have not seen Mme de Villemorin since I was your age, which is about the age she favours. And in the third instance, although I do not deny that Señora Molina y Alcalà Galiano was very kind and generous, Tio Pedro was never so generous to her that she could afford to award the idle interest of a moment gold watches.”

Bungo had to swallow at this last. “No,” he said feebly, recollecting too late that his fashionable brother was now, thanks to his damned marriage, a wealthy man. “Very well, you bought it yourself. But I must say, Luís, there are better things you could be chucking your gelt at! Lord, you’re a family man with responsibilities, now!”

It had taken Luís much longer than he had envisaged to settle all his affairs in Spain—and with Inez’s property to consider also, there had been a great deal to do. So Antonio Luís Harold José Ainsley, “Tonio” to his immediate family, but “Tony,” alas, to Christabel Ainsley, yet another reason for getting both Inez and Pa out from under Paul’s roof, had been born while they were still in Seville.

So Luís now returned tranquilly: “Querido, I am aware of my responsibilities and I have no intention of chucking away anything that should come to Tonio. I did not, in fact, buy this delightful watch with any part of his patrimony.”

“Then—”

“No. Piquet. I took a large sum off—well, a snaggle-toothed Spaniard whom you do not know. About the equivalent of five hundred English pounds; and so I decided to spend some of it on something pretty for myself.”

Bungo sniffed, but appeared slightly mollified. “Well, that’s not so bad. Unless he were Tio Pedro’s bosom-friend?”

Luís’s fine shoulders shook. “Given the context in which we were lately speaking, querido, I cannot but feel that the word ‘bosom’ was ill-chosen, there! It was after Tio Pedro’s death, but as a matter of fact he was more a bosom enemy.”

“You mean you took five hundred pounds off an influential Spaniard of Tio Pedro’s generation? Luís, doing that sort of thing in Seville will earn you a Spanish bullet or a length of Toledo steel in you!”

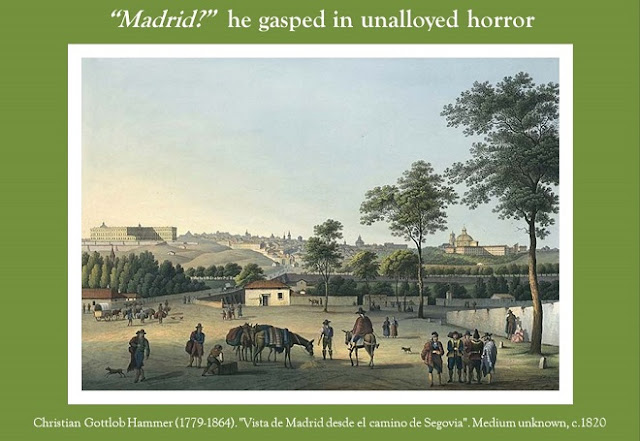

“Actually, it was in Madrid.”

“Madrid?” he gasped in unalloyed horror.

“Bungo, querido, I had merely gone up for the bullfighting with Primo Emilio—you don’t know him, he’s one of Tia Ana’s sons—and poor Juanito: unlike the rest of the family, Emilio doesn’t mind him.”

“You are the greatest imbecile that ever walked!” shouted Bungo angrily. “Madrid’s full of Tio Pedro’s sworn enemies, not to mention damned Pa’s enemies!”

“And Primo Carlos’s political enemies,” added Luís calmly.

“This is NOT FUNNY!”

“Querido, you are exciting yourself for nothing. The Spanish do not challenge one for a mere matter of play. It would have to be political, or a matter of a lady’s honour. And I am neither naïve nor a boy any more,” he said with a slight shrug. “Though I know you and the rest of the family consider me so.”

Bungo had been about to shout at him again. He bit his lip. “No, we don’t, old man.”

“Of course you do: you have all taken your tone from Paul, and I’m sure it’s very natural,” said Luís mildly. “But you see, he still thinks of me as the boy of nineteen whom he knew in Brussels.”

“I don’t think so. Um, well, you came over to see us about a year after that,” said Bungo uneasily.

“Yes. Do you remember how scathing he was about my greatcoat?” he said reminiscently. “Well, it was true it had peaks on the shoulders like the Pyrenees themselves, and—I forget. Something of which the famous Mr Weston would not have approved!” He laughed.

“That,” said Bungo grimly, pointing to the coat which was laid out ready for him, “is not from Weston, out of course!”

“Oh, but naturally: the English tailors are the best in the world,” he murmured.

“Luís, stop changing the subject!”

Luís returned mildly: “I have got out of Spain. Don’t care if I never see Madrid again. And as a matter of fact, now that I am a family man with, as you so rightly mention, responsibilities, I shan’t—well, I don’t say I shall never pick up a card again. But I shan’t be playing piquet with any more rich Spaniards, I can promise you that,” he ended with a wry grimace.

“Oh,” said his little brother limply. “Damn’ glad to hear it. Er—Luís, I wanted a word with you about something different.”

“Yes? –Go on, old man, my valet don’t understand English. –¡Jesus! ¡Venga aquí!”

A thin, yellow-faced person shot in, bowing profoundly. “¿Si, señor?”

“Help me into this coat,” said Luís in Spanish. “—He insisted on coming on the yacht with me. Fortunately he’s a good sailor, not like Paul’s Francisco,” he said to his brother in English.

“What? Never mind that! Listen: although Miss Marianne Formby is a pleasant girl, the father is but a shopkeeper—I don’t know if the Miss Formby you met mentioned that?”

“You have already mentioned it yourself, Bungo. A respectable trade,” he said lightly.

“I think you have not seized my meaning,” said Bungo on a grim note.

“Of course I have seized your meaning: I may not be the brightest one of the family, but I am not positively a dunce. You are trying to say that the charming Miss Marianne is the daughter of a shopkeeper. Well and good: I dare say she would not do for your friend Richard, and I rather think he has realised that for himself. But just let me remind you, Bungo, while we are on the subject of unsuitable parents, that we are the sons of a spy.”

Bungo swallowed hard.

“Go on,” said Luís drily: “tell me that in the wake of Giles’s influence prevailing upon Prinny and Wellington to give Pa a damned medal, the family is completely rehabilitated. I don’t think even Gaetana would grant you that, though she certainly realised that it would enable damned English Society to receive her as Giles’s wife with the appearance of complaisance.”

Bungo went red to the roots of the ginger hair. “Luís, how can you say such a thing?”

“Of my own sister? Who could say it, if not her own brother? I am very sure she would admit it herself, if you asked her. Don’t you see that for any son of Harry’s to set himself above the family of a respectable tradesman is a ludicrous piece of hypocrisy?”

“We— Our generation is—has got past that, Luís,” said his little brother in a shaking voice.

Oh, dear! It had really hit home, and Luís had not, truly, intended it should. Though he had not liked to see Bungo looking down his nose at sweet little Miss Marianne and her delightful mother. “It’s true that you and Paul have become very respectable,” he said kindly, “and of course Maria and Bunch have both married very decent fellows. And I know that your friends from Winchester all accept you as one of themselves, and have been very content, with Harry tactfully out of the country, to treat the whole thing as nothing more than a daring piece of youthful folly that makes a dashed amuthing story. But then, none of them knows the true detailth of Harry’s career, do they?”

Bungo licked his lips. After a moment he said miserably: “Do you?”

“Well, no, and I don’t deceive myself that he would ever tell me everything, either. But if ever I am tempted to believe he ith not as bad as we all believed him to be, back at the time when we were living in Brussels, I remind myself that Paul remembers seeing him with Ney.”

“He could have been spying for our side—and in any case, how old was Paul at the time he claims it happened?”

“Bungo, querido, I had not meant ever to tell you this. But I asked Madre about it—behind Harry’s back, I admit,” he said wrinkling the elegant Spanish nose, “and with a couple of glasses of Marsala inside her, I admit that, also. And she informed me that Marshal Ney was a charming man with delightful manners, who praised her Spanish clear soup with the bitter orangeth.”

“Oh, God,” said Bungo dully.

“Mm.” After a moment he added cautiously: “It still does not absolutely prove that Harry was not spying for the English—”

“Luís, shut it,” said his brother heavily.

Luís was silent, though biting his lip a little and looking at him anxiously.

After quite some time Bungo said bitterly: “I wish to God I had never left India!”

“You had to, dear fellow: your health would not have stood up under the climate.”

“I dare say, but what the Devil is there for me to do here? I fully take your point about Bunch and Maria and their decent fellows—and of course it’s even more so in Gaetana’s case! But a girl marries into a man’s family and out of her own, to all intents and purposes, don’t she?”

Luís had not of course made this precise point, but the thought had most certainly been behind his words—though he was just a little surprised to see that Bungo had seized it so readily without his having to spell it out. “Exactly. It’s quite different for a man. And, just by the by, never mind the coats from Mr Weston and the complaisant ladies, I am accepted by the stuffy English nobility and gentry very largely on account of Gaetana’s marriage: in fact, they all refer to me as ‘Lady Rock.’s brother’.” He shrugged a little. “Paul is very much helped by having the property, of course—but also by Giles’s influence and support. And then, he and Christa are lucky in that neither of them cares for a town life, and are happy just to live on the property.”

“Hell,” said Bungo, gnawing on his lip.

“I would not claim for an instant that there is nothing for you in England, mi querido, and I know Paul and Christa would be very happy if you were to take over one of Ainsley Manor’s farms, but I think you should realithe that it wouldn’t do to set yourself too high. And you do have the option,” said Luís carefully, “of going to Spain. The climate is not near so severe as that of India, and we are certainly free of those ghastly tropical diseases they have out there.”

Bungo’s jaw had dropped. “You don’t mean, to live on the estate?”

“Sí, sí, and to inherit it, of course,” he said mildly.

“Luís, that’s your inheritance!” he gasped.

“That was always the idea, but I no longer need it, and I don’t wish to settle in Spain.”

“I—I couldn’t. I’ve never even thought of it.”

“I know that, querido. But think of it now. I should understand, of course, if you were reluctant to settle in a Catholic country—”

“Uh—well, can’t see that it’d make all that much difference, old man. Well, Pa managed, didn’t he? Never did go much on religion—I mean, one sort’s much like the others, when y’come right down to it. All right for the women, I suppose,” said Bungo with a slight shrug.

In spite of those years Bungo Ainsley had had at Winchester, his brother wasn’t all that surprised to hear this avowal from him. Of the two twins, only Bunch, who was considerably brighter, had ever taken the slightest interest in theological matters. “Yes, well, for me it’s a considerable sticking point, but I agree that in everyday life it makes no difference whatsoever.”

“No, well, thought as much. Lor’, Pa was telling me all about some dashed holy festival they had in the village: trotted the statue of some saint around the square or some such, and him and Madre walked along behind Padre Bartolomé with half the household!”

“Precisely,” said Luís, smiling at him and not asking him if he believed, then, that only the priests had the right to interpret Holy Scripture.

“Don’t know that I’d care to be surrounded by Spaniards all the time, though,” he said with somewhat belated caution.

“Everybody has always been very kind to me, but I can see that after Winchester, and so many years in England, it may strike as very foreign, and you may not care for it.”

“No.” Bungo licked his lips. “So you won’t go back?”

“Not permanently, no. Inez seems happy to be in England. And very happy to be out of her mother’s orbit,” he added drily. “And I would prefer to bring my children up here.”

“Um, that is a point. Well, could send ’em to school in England… No, dammit, Luís, they’d be called damned dagoes!”

“Yes,” said his brother simply, reflecting that it was just as well Bungo had been a pugnacious little boy, very handy with his fists. “If you don’t fancy Spain, I think you should think seriously about taking that farm of Paul’s. I know he’d try to make your decisions for you, despite his best intentions, but I’m sure you’re stubborn enough to stand up to him: you’ve always been much more determined than I. And—though she might not let you choose your own sitting-room curtains—I think Christa would be on your side.”

“Uh—yes, think she would, as a matter of fact. Very sensible woman. And if she wanted to furnish the place for me, so much the better.”

“Bungo,” said Luís, shivering, “her house is full of blue.”

“Uh—well, dare say she does care for the colour. I think she’s got it looking dashed elegant, meself.”

“Blue? In the English climate? –Never mind,” he said with a sigh, as his brother was looking baffled and annoyed. “Just take it that I am a damned dago in that, also!”

“But you don’t wish to live in Spain!”

“No. Then take it,” said Luís, eyeing him very drily indeed, “that I am just a petty-bourgeois.”

After a moment Bungo retorted crossly: “On the level of a shopkeeper, you mean!”

“If you like—yes.”

“You are beyond the pale, Luís! And I more than took your point, earlier!”

Luís looked at him in genuine surprise. “I’m really sorry, Bungo. No, well, result of living with Harry so long, y’see. The man’s incapable of putting anything simply—or if he do, look out.”

After a moment Bungo conceded: “No, well, just for God’s sake don't say anything like it to Richard, will you?”

“No, no, of course not! I don’t think he feels that Miss Marianne’s family is at all a joking matter. I shan’t mention anything remotely related to the matter. Though in his shoes—” He broke off, shrugging. His earlier casual mention of Miss Calpurnia had not met with a kindly reception from either his brother or his respected parent—Bungo crying “Not another!” and Sir Harry grunting: “Only a fool gets mixed up with an unmarried bourgeoise, y’fool.” After a moment he said: “So, shall we go down?”

“Might as well,” agreed Bungo on a sour note.

Luís looked at him rather sadly, but did not take back anything he had said. He had, to say truth, been very disappointed to find his little brother all set to turn himself into the stuffiest of English snobs. Of course the fellow was unhappy with his occupation gone, but that was no excuse for looking down his nose at a dear little girl like Miss Calpurnia’s sister.

Bungo went downstairs frowning. Luís might say what he liked: they were, after all, still Giles’s in-laws, and Paul was, after all, the master of Ainsley Manor with a respectable position in the county. Well, Luís might not be utterly dago-ish, but he was certainly becoming damned eccentric!

Mr Baldaya did not manage private speech with his older sister that evening, but as he knew she usually got up early, he caught her at breakfast before most of the family was up—though Lewis had already gone out to look at one of the farms and perhaps get in a little rough shooting.

Lady Stamforth was breakfasting, as she often did, on curried eggs with a soured milk sauce, dosahs, and chutney.

“Ooh, are they narial dosahs?”

“No, we’ve run out of coconut yet again: Sita Ayah’s used eet up een her huge batch of white barfees for Christmas. Plain flour, Dicky.”

His mouth tightened. “Please call me Richard, I’ve asked you innumerable times. And if you would have the goodness to order the ayahs to do so, I’d be vastly obliged.”

“Dicky—Richard, they’ve called you Dicky all your life, how can I order the poor old theengs to change now? They can’t understand, to them you’re steell Dicky baba!” she cried.

“Nevertheless, please try.” He sat down, helped himself lavishly to curried eggs and took a dosah. “Beet chutney?”

“No, Rani’s plum chutney.”

“Good.” Richard took an enormous portion of it. Placidly his sister rang the bell and ordered up more.

“Look,” he said grimly when he was on his second cup of coffee: “it cannot go on. We met Mrs Formby yesterday—”

“Yes, Luís mentioned eet. She sounds a very pleasant woman.”

“She is a very decent woman indeed,” said Richard, flushing crossly, “and that is my point! You must stop your stupid deception at once! My heart was in my mouth the entire morning for fear Luís would let it out that this ‘Nan’ the Formby girls met was you, and that Jack’s my niece!”

“Goodness, deed you not warn heem? That was silly,” said Nan calmly.

Richard spluttered indignantly.

“After seeing Mouse and Victoria een the town that other time, what made you suppose eet unlikely you would bump eento them again?”

“Nan, I’m warning you, you have gone too far!” he shouted.

“Eef you had not met Mrs Formby—”

“We DID!” he bellowed.

“Yes. You weell just have to avoid the town,” she said serenely.

His mouth tightened. “That will not be a hardship: that market was damned boring.”

“I always love eet. But eef you would like to see Mouse again—”

“No!” he snapped, going very red.

“Oh? Bungo, then,” said Nan calmly.

“What? No! Well, I dare say he did admire her at first, only—”

“He has had time to realise that her father keeps a shop,” said Nan with the utmost placidity. “Yes. He ees by the far the most conventional of all that family.”

Richard was very flushed. “I dare say it is that, and it is most certainly a consideration!”

“Our own father was een trade for years een India. Added to which, he eloped with Mamma, and een the case you have forgotten eet, eet was only by sheer luck that hees poor wife died and he and Mamma were able to marry before I was born.”

“That is ancient history!” said Richard, very red.

“To many genteel English families, on the contrary, eet ees not: eet ees vairy recent history. I don’t deny that Lewis’s having married me makes a great deal of difference—to the sort of person,” said Nan, her little straight nose wrinkling in distaste, “to whom social forms are more eemportant than morality, honesty, and solid worth. –I know you have forgotten since we came to England and you went to Winchester that I have a mind, as well as conveniently forgetting Mamma’s vairy blotted copybook, but there you are.”

“Are you saying that any offer from me would not be acceptable to a genteel English family?” he said through his teeth.

“Not quite that. I do theenk they might hesitate, Di—Richard. But that was not my point at all, and I am sorry you took eet that eet was. My point was that we are the children of a man who was een trade, just as much as the Formby girls, and that our immediate family history ees far, far less respectable than any decent English shopkeeper’s could ever be.”

“The Baldayas,” said Richard through his teeth, “are most highly thought of in Portugal!”

“Not Papa’s branch. Dear old Uncle Érico’s family ees, of course. But eet was only hees eenfluence, together weeth the size of our fortunes, that made the Portuguese Embassy een London accept us weeth complaisance—and at that, you know, the dear old man had to come to England een person to ensure they deed. I theenk perhaps you deed not realise, being only a boy at the time, and I’m vairy sorry that I deed not theenk to explain eet all to you.” She looked at his scowling face, and sighed. “My dear, just take eet that we have no cause whatsoever for any family pride, and—and nothing to justify any sort of prejudice een regard to an honest, hardworking family who own a shop.”

Richard thought it over. “I see,” he said in a choked voice.

Nan sagged. She had just realised that she had coupled the words “pride” and “prejudice” and she was afraid he might have been about to accuse her of turning the thing into some sort of literary joke. “Yes.”

He got up, looking very bitter. “So you wish to see us ally ourselves with the small shop-keeping class, do you?”

“That ees not what I meant at all! Eef you truly felt for a girl from that class, I would not see any objection—all I wanted you to see was that there could be no objection!” she cried. “Eef anything the objection would be on the girl’s family’s side, once they had heard about our parents!”

“Yes. Well, it was pretty obvious even to me, though I might have been just a brat when we came to England, that it was a dashed bitter pill for Cousin Keywes to swallow,” he said sourly.

Nan did not point out that Robert Jeffreys, Lord Keywes, had an extremely conventional mind and must be one of the greatest prudes in England. She merely said: “Exactly.”

He went out, his mouth tight, scowling.

“Are you seeking my approval?” said Stamforth at the conclusion of Nan’s report, his eyes twinkling.

“Yes,” she admitted frankly.

He put an arm round her, smiling. “Well, you have it, my darling, for what it’s worth. I don’t see how anyone could have put the thing more clearly or fairly.”

“Oh, good,” said Lady Stamforth limply.

“Er… I gather you didn’t get the impression that Richard might go so far as to consider little Miss Mouse good enough for him after all?”

“I don’t theenk so, Lewis, alas,” replied Nan with a sigh. “But I weell say eet: I theenk that Mouse would be vairy suitable for heem, for she ees sensible and vairy bright! And most unlike the usual simpering débutantes!”

Lewis passed a hand over his straight, thinning iron-grey hair. “And believes you to be a half-Portuguese serving-woman,” he noted.

Nan scowled, looking, in spite of the charming afternoon gown, extraordinarily like the pugnacious Jack.

“At least the half-Portuguese bit is true,” he noted drily.

“I could say eet was all a meesunderstanding!” she said eagerly.

“According to Amrita and Jack, you actually told her you were your own servant.”

“No!”

He raised his eyebrows. “Oh?”

“I— She said she had thought we were half-Portuguese servants and I conceded we were half-Portuguese,” she said, pouting.

“Yes, well, any court in the land would hang you on it, Nan.”

She sighed. “Perhaps I could call on them and confess eet all, and—and throw myself on their mercy.”

“Mm. After Christmas, perhaps.”

“Eet weell not ruin their Christmas: why should eet?” she cried.

“It might ruin mine,” admitted his Lordship, shuddering.

Nan gulped. “Oh. Vairy well, I shall wait and—and see eef he mentions her again. But to be honest, I doubt that he weell. –I should never have sent heem to Weenchester!” she burst out bitterly. “I thought, since eet was Hugo’s old school, eet must be the theeng!”

“Of course, my dear: it was the thing,” said Lewis calmly, not expressing his thought that the expectable consequence of sending the lad to Sir Hugo Benedict’s old school was that he would emerge from it something very close to a facsimile of that pleasant, conventional, English country gentleman. –Lewis had never met Nan’s late husband, Jack’s father, but then, on the whole he had not needed to. Nan had never criticised him, and it was obvious that her brothers had both admired him tremendously. But, though he had had a considerable sense of humour, and of course had overlooked the family history—the which Lewis Vane did not think for a moment would have been the case had Nan been under consideration for the baronet’s first wife rather than his second and had he not already had an heir—it was clear enough that he had been very typical of the class to which he belonged. Lewis Vane, Viscount Stamforth, did not think any the less of him for that: how many human creatures had the capacity to rise above their upbringing and circumstances?

“Mm?” he said, jumping slightly.

“I said,” said Nan with a sigh, “that Cousin Tobias ees lying down before dinner.”

“Er—full of tea and cakes?” he groped.

“No—well, probably, yes! M. Lavoisier sent up four different big cakes thees afternoon, and five leetle plates of small ones. Um, no, I just wanted to warn you that tomorrow he ees determined to ride out weeth you, so please don’t leave at crack of dawn.”

“Could I not leave at crack of dawn, get the stuff done, and then come back for him?” said Lewis plaintively.

“Vairy well!” she agreed with a gurgle.

“Good. –Nan, may we go up to change for dinner?” he said with a sigh.

Nan bit her lip. “Miss Gump and the girls are not yet back from Brighton.”

“The hen will have bumped into another hen and started gossiping,” he said grimly.

“Mm. Oh, vairy well, then, we shall have ours. And I am sure the boys—” Nan broke off, swallowing. “I keep theenking of heem as a boy, and he ees so annoyed that I cannot remember to call heem Richard! But eet’s no use expecting the ayahs to change: they’re too old and set een their ways, and—and they can’t understand, Lewis!”

Placidly Lewis replied: “No. I’m sure the boys are starving, too—even though, as Lady Rockingham so kindly warned us not to, I didn’t drag Bungo out with the guns this morning.”

“No, and eef you had done, I theenk there would have been more than two rabbits and a crow een the bag!” retorted Nan swiftly.

He sighed. “Very well, I shall confess. The crow was because I was showing off to Jack.”

Nan gulped.

“Feet of clay,” he said sadly, shaking his head.

“Dead-eye Dick, more like!” she returned with a sudden laugh. “Come along, then, we shall dine een twenty minutes!” And she hurried out.

Smiling, Lewis rang the bell and informed the magisterial Troope that they would dine in twenty minutes whether or no the young ladies and Miss Gump were back—whereupon Stamforth Castle’s butler bowed smoothly but was seen to exit with a very satisfied gleam in his eye. There was not a male in the place who could stand Miss Gump—and as a governess, she was, of course, useless—but Nan claimed she was unswervingly loyal and it would break her heart to be dismissed. Oh, well; it was, after all, a very small price to pay for the privilege of being married to the Portuguese Widow! Stamforth hurried upstairs with a twinkle in his eye. Nutting and mushrooming expeditions and Portuguese petticoats and ludicrous masquerades as her own serving-woman—not to mention the warmest heart in the kingdom! The idiots of the Upper Ten Thousand who had dubbed his Nan “the P.W.” did not know the half of it—no, not an hundredth of it!

Julia thought the matter over for some time and finally decided that young Mr Ainsley had definitely been warning them off his brother and there was something very odd about the thing. And of all the family, who was it who got about all over the district and would be most likely in the first instance to have bumped into a stray Spaniard—well, half-Spaniard, whatever the man was, same difference—and in the second instance, not to have breathed a word on the subject? Added to which, Captain Cutlass’s manner over the last week or so had been… odd. Well, she had nothing in common with Victoria, and was irked at being urged to spend some time in the girl’s company, true, but… She found Captain Cutlass in the front parlour, sitting by the cold grate. Odd in itself, quite.

“Dear, you haven’t even lit the fire!” Captain Cutlass didn’t move, so Julia bustled over and lit it herself. “That’s better!” She sat down opposite her. “Captain Cutlass, I have to say this. On the day Mouse and I bumped into the young gentlemen from the castle, Mr Bungo Ainsley mentioned—in the most pointed manner, really, I have to say it—that his older brother, Mr Luís, is married.”

To her dismay, Captain Cutlass went very red. “That cannot be of any relevance to New Short Street!” she snarled. Suddenly she bounded up and rushed out of the room. Her footsteps pounded up the stairs. Then the bedroom door slammed.

Julia swallowed hard. “Oh, dear!” She went on sitting by the fire, staring into it blankly, for some time.

Then the door opened. “Get this down yer,” ordered Cookie, proffering a cup of tea.

“Thanks, Cookie, dear,” said Julia weakly, trying to smile.

Cookie sat down opposite her and waited until half the tea had vanished. Then she said: “I ’eard ’er belt upstairs.”

“Mm.”

“Think she’s a-bawling.”

“Mm.”

Cookie’s shrewd eyes twinkled. “Never mind if this particler one’s a gent or a brother-in-law to a h’earl or a viscount or what: on the ’ole ain’t it a good sign, Mrs Julia, deary?”

Julia blinked at her.

“Well: Captain Cutlass, what ain’t never glanced twice at any of the pretty lads from the town, a-bawling over a man?”

“Oh, good grief, you’re right!” she said with a weak laugh. “Of course it is!”

Next chapter:

https://thefortunateformbys.blogspot.com/2023/10/a-formby-christmas.html

No comments:

Post a Comment